Silicon Valley Bank: Traditional Finance Risk

The contagion risk related to Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) 's takeover by federal authorities has sent shock waves through traditional finance and cryptocurrency. SVB has served as the go-to bank for Venture Capital and has become known as a leading bank for start-ups and their investors. SVB is the 18th largest bank in the US, with over $212 billion in assets. Let's be clear this is a legitimate institution that failed.

The immediate effects played out within hours when USDC, a Stable Coin issued by Circle, had treasury funds with SVB and was de-pegged on March 11th, 2023. Circle spreads funds across numerous Banks, already illustrating that they see significant risk in using a single institution. Many of the other affected companies also maintained multiple banking partners.

One of the critical differences between Circle and Silicon Valley Bank is the type of instruments they hold to store customers' cash. According to their Blackrock Portal, Circle has stuck to Short-Term Bonds from the US Government that are liquid and mature on a weekly rolling basis in order to access capital. Short-Term Government Bonds are much more liquid than Long-Term Government Bonds and generally maintain their value. It states in Blackrocks Portal that these figures are self-reported. An independent audit would be necessary to trust this data.

In times of uncertainty, remaining adaptable and avoiding long-term commitments may be a good idea. If a cryptocurrency company holds Short-Term Government Bonds instead of long-term investments that must be held to maturity, they can react to the changing financial landscape more quickly. Additionally, the US government can print more money to cover its debt and bail itself out of trouble. It appears that Circle mitigated some loss with this strategy.

According to their current numbers, Circle suffered a 3.3 B loss due to SVB, about 7.5% of their total 43B funds. Past FDIC takeovers saw more than 80% recovered and access to a portion of capital quickly, and Circle should see a similar outcome. Circle presents a basic framework for mitigating risk with Traditional Finance by using multiple depository institutions for a percentage float amount. SVB could have avoided some trouble by placing the bulk of its capital in Short-Term Government Bonds that mature frequently. (Update: FDIC plans to cover all deposits although executives and investors will still bare the loss.)

Contrasts between Circle and Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) can take time to decipher. Reports suggest that Circle is finding success, yet the USDC not covered by FDIC deposit insurance may still present a level of risk, leading to possible redemption requests, notwithstanding Circle's efforts to persuade clients of the safety of their product. Making the situation further complex, the simultaneous release of SVB assets and those held by the Federal Reserve under the mortgage-backed security program could have wide-reaching implications. Even with the FDIC working to reduce the losses from selling HTM securities if needed, it could still lead to tighter lending conditions and a more negative attitude toward the mortgage market from investors.

When the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) takes over a failed bank, it generally assumes control of its assets, including its held-to-maturity (HTM) securities. As it turns out, SVB was heavily invested in HTM mortgage-backed securities (MBS) valued at $57.7 billion.

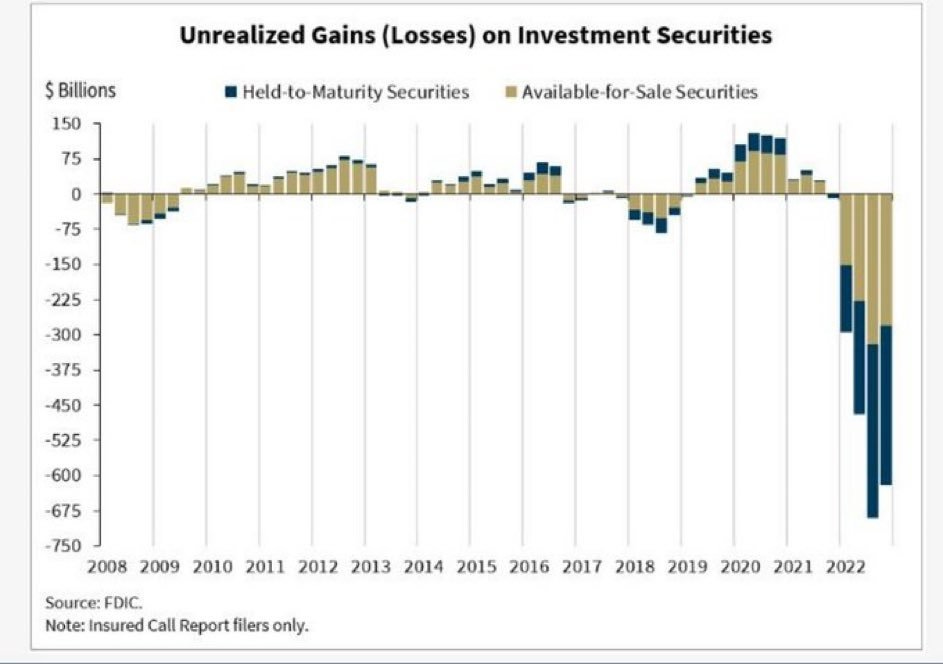

Under normal circumstances, HTM securities are intended to be held until maturity and are accounted for on a bank's balance sheet at amortized cost. This means that the bank is not required to adjust the value of the securities based on fluctuations in their market value but instead recognizes interest income over the life of the security. For this reason, the magnificent unrealized losses weren't immediately evident to the general public, and SVB was rated one of the best banks in the country only days before its collapse. If we start to re-examine other banks based on these unrealized gains, the picture becomes bleak.

When a bank fails, the FDIC may be forced to sell its assets, including its HTM securities, to recover as much money as possible for its depositors and creditors. In doing so, the FDIC is subject to the same accounting rules as the failed bank, meaning it must account for the securities at amortized cost.

If the FDIC sells HTM securities at a loss, it may be required to recognize the loss on its balance sheet, which could impact its financial stability and ability to fulfill its mandate of insuring deposits. Therefore, the FDIC generally tries to minimize losses when selling HTM securities and may hold onto them until maturity or until market conditions improve.

A bank or other financial institution selling HTM MBS can affect the supply of available mortgage credit. If the sales are significant enough, they could tighten credit conditions, making it more difficult for borrowers to obtain financing for home purchases. Tighter lending and higher interest rates could lead to a decrease in demand. Additionally, if the sales of HTM MBS result in a significant decline in the value of these securities, it could negatively impact investor sentiment and confidence in the mortgage market. It is unclear whether the Federal Reserve's decision to reduce its holdings of mortgage-backed securities (MBS), which it has been accumulating since 2008 alongside the sale of SVB's MBS investments will increase the impact of the Silicon Valley Bank FDIC takeover.

Ultimately, the impact of such a scenario on the housing market and the broader economy would depend on various factors, including the size and timing of the MBS sales, the strength of the economy, and the overall level of investor confidence in the financial markets.

Overall, while the unwinding of the Fed's MBS balance sheet could impact interest rates and the housing market, the actual magnitude of this impact is difficult to predict with certainty and would depend on various economic and market factors. Since multiple factors are at play, knowing precisely how it will turn out is impossible. This is only one of many opinions and should not be considered financial advice. We can learn from SVB’s failure and use the insight to be aware of similar situations in the future.

The information in this article is provided for general informational purposes only and should not be construed as professional, legal, financial, medical, or other advice. You should consult with a qualified professional for advice tailored to your specific circumstances. The author and publisher disclaim any liability for actions taken based on the content of this article.

Author: Amber Rhoden